The following is an excerpt from the site http://www.tellusconsultants.com/Thread/ACANTH.HTM, showing the negative effects of overkilling of one species using the crown-of-thorns starfish as an example. It may be quite long though, so try speed-reading or just focus on the important points.

Out of Control

Cancer. The web of intercommunication between all the microscopic cells of a human body keeps the old system humming along. If some of the cells stop hearing the music and start replicating themselves too quickly, they can go into a feeding frenzy, eating everything they can get their little membranes around. And the great idea that was the individual being consumes itself from the inside out.

Coral reefs get cancers, too, and one of the most interesting of coral reef cancer stories is that of the crown of thorns starfish.

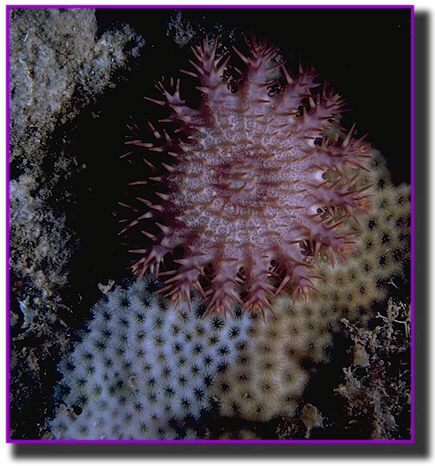

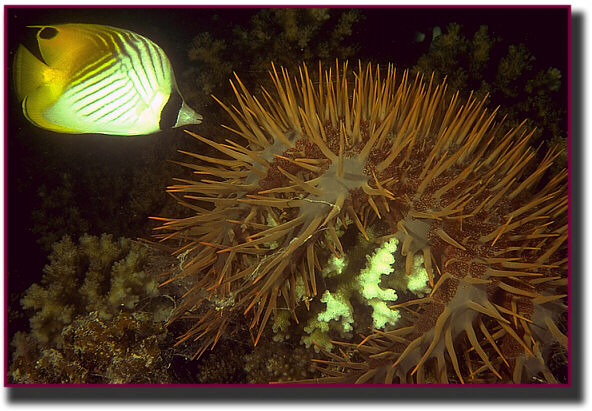

By most people's standards, the crown of thorns, Acanthaster planci, are ugly. They have 16 to 18 arms and are covered all over with long, venomous spines. A big one can be half a meter in diameter.

An electron microscopic picture of the tips of their spines show a molecularly sharp crystal point. The spines are so sharp they slide through skin, and most gloves, without any real pressure; just glide in. Then the venom - a nerve toxin - gives exciting lessons in why one should leave these starfish alone.

The effects can last a long time. One lady on my control team in Guam got spined in her thumb and her thumbnail grew out crooked for months afterwards.

Crown of thorns starfish are found on coral reefs in the tropics ranging from the Red Sea, throughout the Indian and Pacific Oceans, and all the way to the Pacific coast of Panama. They eat coral. Not the coral skeletons, just the delicate coral polyps. Since coral flesh is just a thin film on the outside of the coral skeleton, and since the polyps can withdraw down into protective little cups, coral is not very easy to make a meal out of.

A hungry starfish climbs up on a coral and pulls its stomach out of its mouth with its tube feet. The starfish has thousands of these flexible tube feet, each ending with a little suction cup. The feet pass the stomach from one to the next until the big yellow stomach is spread out over the coral. Then the stomach slooshes the live coral with digestive juices. The cells of the stomach scoff up the bits of dissolving coral. When the starfish has cleaned the coral right back to the white calcium carbonate skeleton, it sucks in its stomach and walks off, using those tube feet.

Normally, there are not very many Acanthaster on a coral reef. Maybe one every kilometer of reef or less. Many reefs don't seem to have any at all and, of course, the starfish is absent entirely from Atlantic coral reefs.

Usually, they live near coral reef passes. Maybe they help keep the passes open by trimming corals. Maybe they just like the current. Back before the sixties, not many people had ever seen or heard of the crown of thorns starfish. The diving biologists of the forties and fifties surveyed many miles of coral reefs and even very experienced diver/biologists had never even seen one.

Then, in 1962, reports of a strange bloom of these creatures surfaced from Green Island, just of Cairns in Queensland Australia.

The Queensland government asked Dr. Robert Endean, an Australian marine biologist who specialized in venomous sea creatures, to check it out. He returned from the field with tales of millions upon millions of starfish devouring the coral reefs around Green Island and other reefs on the Great Barrier Reef. He urged instant action. The government buried his report. He went to the press. The government said Endean was exhagerating, there was no problem, not really. Bob, furious, escalated the controversy but in the end, his report stayed buried until, years later, I managed to get the US State Department to request the report under a scientific trade agreement. The starfish did not care one way or the other.

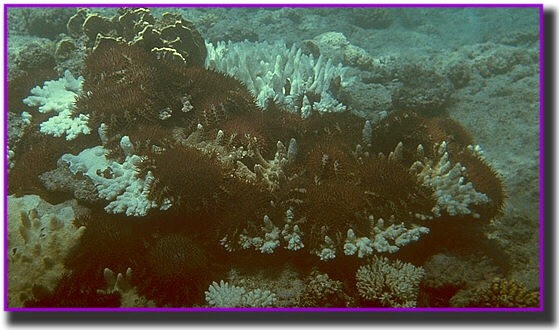

As a specialist in coral reefs and echinoderms (starfish included) I discovered another infestation in Guam in 1968. It had been in progress for perhaps three years when I arrived at the University of Guam. The biologists recognized the reefs were in trouble, but were not sure what the problem was. I knew what was wrong the instant I saw the crown of thorns there on the reefs of Guam. Lots of them. Thousands. Hundreds of thousands. Stripping the living coral from the intertidal zone to the depth limits of coral growth at the rate of one kilometer of shoreline a month. There were two fonts, moving out from an epicenter at Tumon Bay. Ahead of the front the coral was alive. Behind the coral skeletons were bare, slowly being covered with a gray algae. The colorful coral reef fish moved ahead of the bands of starfish, trying to remain in their adaptive habitats, uncomfortable in the dead coral environment. The stripped reefs looked desolate, colorless, compared to the unharmed reefs.

So why? What causes a normally uncommon coral reef predator to become so abundant and overstrip it's environmental limits? Why were they out of control?

I organized a survey of the north Pacific from Hawaii to Palau, and the Northern Marianas Islands to Kapingimarangi. The expedition was supported by the U.S. Department of the Interior and managed by Westighouse Ocean Research Laboratories. I headed a team of 69 diver/scientists that were divided into groups of 10 and sent out to survey conditions in as many locations as possible.

We found other infestations of crown of thorns starfish in different stages of development in many island areas - usually in close proximity to villages or urban areas. There was no "common denominator" to clarify the cause of the population blooms. Instead, the picture that emerged was that blooms are likely to occur where the reefs are stressed. And the reefs of the world are stressed by many different causes.

What sorts of things stress reefs? People blast reefs with dynamite, and the crown of thorns, and even their swimming larvae, are attracted to the metabolytes reseased by damaged corals. People break coral when walking on reefs, to get shells for tourists, to get coral rocks for building material. Reefs are overfished. At least two species of large fish eat the crown of thorns. They are gone from most reefs near people. People poison the reefs with various chemicals to kill or stun fish. Agricultural chemicals applied to island gardens or used to control mosquitos wind up in the sea, and in the corals. This weakens the corals. When the crown of thorns eats the coral they accumulate these chemicals in their own tissues (it does not seem to harm them, the larvae actually survive better with DDT in the water). The predators of the crown of thorns, including triton shells and a beautiful little shrimp, may die or encounter breeding problems from the concentrated poisons in the starfish's flesh. Increased concentrations of carbon dioxide in the sea water reduces calcium deposition, slowing coral growth.

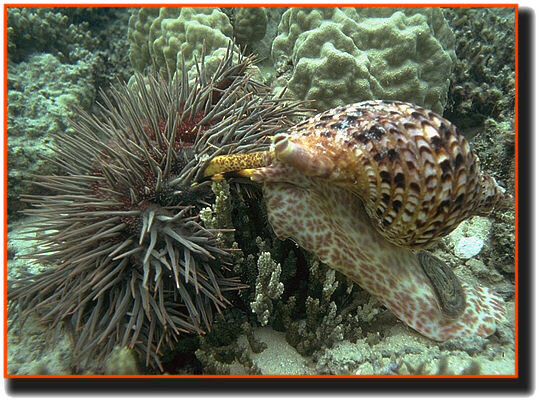

And then there is the triton. The beautiful triton.

Bob Endean said, right away, that he thought that the cause of the starfish explosion was because the tritons were overcollected. Other biologists, including me, thought this unlikely. But now, after investigating the infestations nearly 30 years, I think Bob was right after all. Or partly right. Certainly the tritons are the major predator on the starfish. And they are overcollected, even endangered or locally extinct, in most areas of the Pacific.

There may be many contributing causes of the infestations. Like cancer. But the plight of the triton is symmetrically balanced with the escalation of starfish numbers.

Everybody loves the triton. Or at least they love its shell. People make horns, bookends, door stops, or just decorations of these glorious shells. They sell for as much as $100 for a nice one, sometimes more. Virtually every single island diver, man, woman or child, grabs every single triton they see. A multitude of recreational and professional skin and SCUBA divers grab every one, regardless of size, sometimes just happening across one, sometimes avidly seeking them out.

Tritons normally come out to feed at night. Just as the Crown of Thorns normally feeds at night. These days, most island spear fishers also go out at night and underwater flashlights are found in the smallest island village stores.

They are not hard to see, either. Even small tritons stand out sharply against the background of a coral reef. Glorious colors and graceful shape.

In Florida, at a Shell Factory I found thousands of tritons from all over the Pacific. From tiny little ones only as long as my thumb to big ones the size of my forearm.

The biggest tritons make the most eggs. Big ones are quite rare now. I have interviewed older divers in many islands of the Pacific and they all agree that the triton population has gone down to practically nothing.

Yet you can still find them in shell shops and in markets, getting fewer, smaller and more expensive each year.

The reason I think the triton is especially important in this whole crown of thorns problem is because the triton/starfish relationship is easy to understand, easy to sympathize with, and - in theory - easy to do something about.

After all, nobody NEEDS to kill tritons. The only reason we kill them is because they are beautiful and we like to have their shells for decorations. On the other hand, they are key species and killing them endangers the whole coral reef ecosystem.

The people who live on the islands rely on the coral reef ecosystem for fish and other protein. The small amount of money a few individuals might make selling a triton they found will in no way compensate for the loss of protein for the whole community following a crown of thorns attack. American Samoa spent nearly half a million dollars just fighting the starfish. Every sale of every triton ever collected from their reefs did not total that much money.

So, logically, you would think it would be easy enough to do something about this aspect of the problem.

You would think the island governments would leap to the rescue of the triton, banning collection and sales.

In Australia, the government did just that. But it still permits importation of tritons from other countries, like the Pacific islands, and there are plenty of tritons in gift shops just inland of the Great Barrier Reef. There is no way to know if they came from the Great Barrier Reef or Fiji, is there?

In Fiji, tritons are protected. But almost every gift shop has a few and you can find them for sale in the public market. Nobody has ever been fined or even had their triton confiscated in Fiji. Nobody.

Tonga will not protect its tritons because, "People like them. It's tradition." Nobody would enforce a ban anyway.

CITES. Biologist Ann Paulson and I managed to get Australia to propose listing Tritons on the Convention against International Traffic of Endangered Species (CITES). Japan objected, and Australia withdrew it's suggestion.

Scientists have spent millions of dollars investigating the Crown of Thorns.

The vast amount of scientific research on the crown of thorns over the past 30 years has been very interesting. Scientists are now spending more millions investigating coral bleaching, and a host of coral diseases that flourish in the wake of human abuse of the coral reefs.

As science learns more about the control systems that regulate the population explosions of the crown of thorns, the concensus is finally showing that somehow, perhaps in many synergistic combinations, human abuse of the coral reef ecosystem is behind the problem. Or at least making it worse. A conclusion reached 30 years ago but gradually gaining acceptance.

30 years ago the Queensland government did it's best to sand bag the whole problem. I suspect, the politicians realized something right away. Something the scientists have still not thought of, even though it is pretty obvious.

The control system that is out of wack is larger than the control web in the oceans.

The problem is not the triton, it is the society that collects the triton, killing them because people adore their beauty. Focus on that. How do you reconfigure that control system?

Going back to the cancer analogy, we know smoking contributes to human stress. We know it results in cancer as well as a host of other diseases. Nobody NEEDS to smoke. But people like it, and do it even if it is against the law. See the parallel? Here is the problem to solve. Here is the control system out of wack. Scientists can study the details of coral reef demise for the next 30 years, spending millions to confirm and reconfirm the obvious. So? How will that solve the problem?

And while you are thinking about this, check out the rather obvious link between the population explosion of the starfish and the population explosion of humans, including tourists, in the Pacific tropics. The crown of thorns is not the only population out of control. How do you solve that?

No comments:

Post a Comment